Weird things about disabilities in the movies (Part 1)

Why is “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” so popular?

I’m teaching a class on Disability in Media & Literature at Wm. Paterson University this semester, and it focuses on representation, authenticity, and accuracy as well as hot-button topics like inspiration porn and cripface. In the process of putting the syllabus together, two topics related to the depiction of disability in the movies struck me as particularly weird. This is the first one.

Early in the semester I gave a session over to two classic, well-known examples of disability representation in 19th century literature, Victor Hugo’s 1831 novel Notre-Dame de Paris that we all refer to as The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and the 1843 novella A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens.

The Dickens is relevant because of his depiction of Tiny Tim, the young boy who has a serious unnamed illness that causes him to walk with a cane and will be fatal unless he gets the right medical attention. Tim is used primarily as a prop, “an idealized but pitiable stereotype of disabled people [that] contributes to the idea that disabled and poor people deserve pity and charity,” as Grace Lapointe puts it in Book Riot.

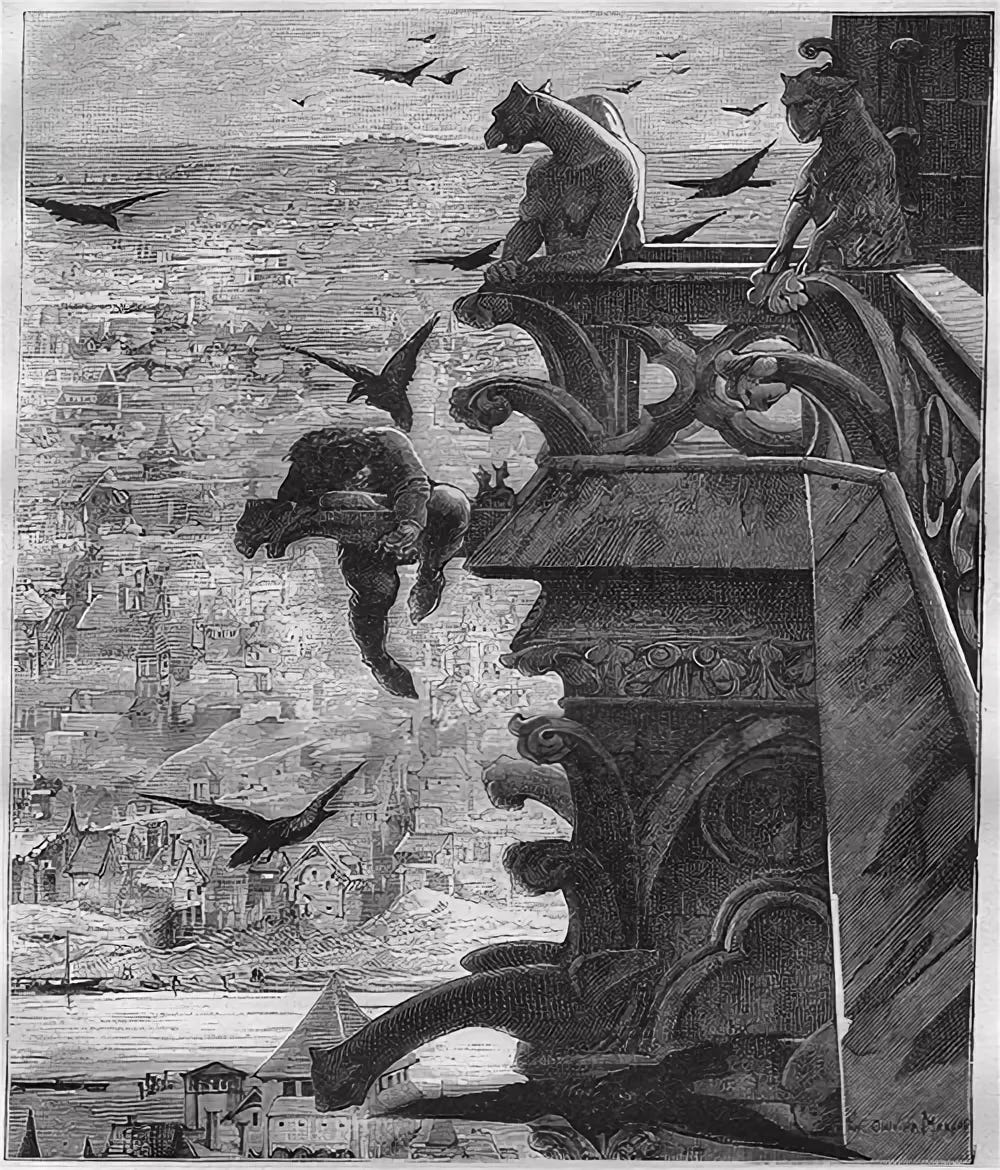

But it was the Hugo that intrigued me. As I put my notes together for the class it hit me how ridiculously popular his tale of the deaf and disfigured church bell-ringer has been, from original publication to the present day (including a Disney animated musical version!). And for the life of me I can’t understand why. I’m really curious about it.

The story

We all think we know the story of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, but we’re probably wrong (especially if that Disney version is your primary reference, although, as we will see, it is not the most egregiously weird adaptation). It’s unlikely you read it, despite it being a classic of French literature, since it is in three volumes, for a total of 940 pages, and is relentlessly brutal and sad, and basically everyone dies at the end.

So here is my summary of the story. You can skip this part of you want, but it is worth it to finally know what the real story is. I’m warning you, it is super melodramatic.

It is 1482 in Paris, Louis XI is on the throne. There is a 16-year-old Roma dancer named Esmeralda who is insanely hot and every man in the city is woozy over her and inflamed by her dance moves. The four guys we care about most are: Captain Phoebus de Chateaupers of the King’s Archers, who seems like an upstanding military chap but is really a punk; the poet and playwright Pierre Gringoire who for some reason Hugo based on a real person; the Archdeacon Claude Frollo, based in Notre Dame cathedral, who is being driven out of his mind because he swore a vow of celibacy but damn that Esmeralda and her moves; and the cathedral’s bellringer Quasimodo, who Frollo saved as a child and sort-of adopted. They all lust after the Roma dancer and get in each other’s way about it.

Quasimodo wins the contest for ugliest person in Paris, which based on the description he would win every year: he has a hunchback and twisted legs, a giant wen covering one eye and bushy red eyebrow half-covering the other, rendering him mostly blind, and ringing the cathedral bells has made him deaf. Everyone is so swept up in crowning Quasimodo the victor they pay no attention to Gringoire’s new play, which pisses off Gringoire no end.

Frollo, which sounds like a chewy candy bar, gets things going by ordering Quasimodo to help him kidnap Esmeralda because that seems like a smart idea. Gringoire, which sounds like a sharp cheese, tries to protect her but Quasimodo conks him good. Phoebus, which sounds like a European electric auto maker, saves her which makes her fall in love with him. Still woozy Gringoire stumbles into the Roma neighborhood, they’re going to kill him cause he’s a stranger and Roma kill strangers apparently, and Esmeralda saves him by agreeing to marry him, so he wouldn’t be a stranger I guess. But she tells him it is a marriage of convenience only, no touching, no kissing, no nothing. Gringoire is pissed off yet again. By the way, Gringoire is kind of pals with Frollo; this becomes important later on.

For his troubles Quasimodo is flogged and put on the pillory to be humiliated in public. This is the famous scene you’ve viewed a million times from the movies. He gets really thirsty, Esmeralda gives him water, and now he’s deeply in love with her.

Frollo could intervene since he’s the one who was behind the attempted kidnapping but he says nothing, which will become a pattern. His dabbling in alchemy and the darker arts starts to get out of hand. Think Anakin turning into Darth Vader, but due to extreme horniness.

Things get murky, plot wise, and start to sound like a second-rate TV soap opera. There’s a thing about Esmeralda’s goat Djali, which is important to her and makes Gringoire jealous because she likes the goat more than him. Meanwhile all Esmeralda can think of is Phoebus, and the two of them arrange to meet at an inn. Frollo gets wind of this and follows them. Esmeralda wants Phoebus to marry her, but he just wants to get into her pants, which he does, and boy does that make conflicted, frustrated Frollo mad. He stabs Phoebus, and Esmeralda sees him do it but of course she doesn’t know who he is.

Since Esmeralda is with the body, and she’s Roma, everyone assumes she tried to murder Phoebus and, for good measure, accuse her of being a witch, too. Thing is, Phoebus isn’t dead, and he could clear things up but it would expose his behavior and maybe threaten his coming marriage to some wealthy stuck-up girl. They torture Esmeralda until she confesses. Frollo comes down to the dungeon and instead of doing the pious thing and confessing it was he who attacked the captain, tells Esmeralda he loves her and will get her out of prison if she promises to love (wink, wink) him back. Thing is, she recognizes him as the person who killed Phoebus and tells him to go pound sand. This is arguably not a good tactical move on her part.

They take Esmeralda out to the square to hang her and just in time Quasimodo swings down, scoops her up, and spirits her into the cathedral where she has sanctuary for a time. Frollo is completely losing it at this point. He tries to rape her but Quasimodo conks him good.

The book sort of descends into shenanigans and chaos at this point. Frollo tells Gringoire – remember him? – that Esmeralda’s sanctuary is about to expire. Gringoire tells the Roma, who put together a small army to rescue her. Quasimodo fears they are there to hang Esmeralda and he fends them off. The king sends guards to fight off the Roma and, by the way, to grab Esmeralda and hang her right away, to get things over with so everyone can go back to their lives of squalor and despair.

In the midst of all this Frollo and Gringoire kidnap Esmeralda. They split up, and Gringoire decides he would rather have the goat, Djali – remember the goat? Gringoire really likes the goat now – leaving Esmeralda with Frollo, who makes one final attempt to seduce her. Again she tells him to pound sand.

Frollo says, okay, that’s the way you want it, then you’re going to hang. Things get a little zany. Frollo tosses her in with Sister Gudule, who is an anchoress, while he goes off to tell the guards where Esmeralda is.

(Fun fact: An anchoress is a woman who has willingly shut herself away, permanently, in a cell where she spends the rest of her life in solitary prayer and contemplation; the male version is called an anchorite. You’re okay unless the people assigned to bring you food and take away your poo forget to come by.)

Anyway, Gudule isn’t happy about this, not only because it disrupts her groove, but because Esmeralda is Roma and Gudule hates all Roma because she believes the Roma stole her daughter and ate her. But, and I’ll bet you can see this coming, Esmeralda turns out to be Gudule’s long-lost daughter with the much less cool name of Agnes. The Roma kidnapped Agnes to swap her with a Roma baby that was born with disabilities. Guess who that was?!?

The mother and daughter reunion is short-lived, as the guards come, Gudule is killed, they take Esmeralda to the square in front of the cathedral, and hang her. She’s dead, bam. Phoebus watches with his wealthy fiancé and doesn’t care. Up above in a cathedral tower Frollo watches, laughing and satisfied. Quasimodo is with him, and is grief-stricken by the death of the woman he loved, so he tosses Frollo from the tower, to a squishy and well-deserved death on the steps below.

Quasimodo disappears. His skeleton is found years later, lying beside that of Esmeralda. Gringoire – remember him? – goes on to be a successful playwright. Not sure what happens to Djali the goat. The end.

Amazingly popular in the movies

The book was a great success due to its sensational plot, and its scope and breadth of characters. It was immensely influential in its presentation of all strata of society. It dealt with universal themes including lust and love, the abuse of power by the church and the military, and the inequity of bigotry and class differences. It made a strong point about the ugliest character being the most caring and generous, while the handsome member of the military, and the church leader, are the two most vile. And, with the uniquely different Quasimodo, it fed into the 19th century fascination with the strange, the different, the disturbing.

The Cathedral of Notre Dame is in many ways the protagonist of the book, silently witnessing everything that happens, and the way Hugo treated it brought increased attention to the value of gothic architecture and the importance of preserving great examples like the cathedral. The first opera based on the book appeared in 1836, with a libretto by Hugo himself. The first ballet appeared in 1844, and the first stage play in 1861.

But all that is about the 19th century, not the 21st, so it doesn’t quite explain its continued popularity up to the present day. Especially regarding its adaptation as a popular feature film.

The first film adaptation was from France in 1905, titled Esmeralda. Ten minutes long, it focuses on the dancer and Quasimodo. It was directed by Alice Guy-Blaché who was a pioneering woman filmmaker, some say the only professional woman filmmaker in the world at the time. Only a few blurry images survive, but Quasimodo looks like a panda in them.

The French also made a 26-minute version in 1911 called The Hunchback of Notre Dame that was amazingly faithful to the story, considering the running time.

The Americans got into the act in 1917 with the 60-minute The Darling of Paris. It is a lost film, destroyed in the 20th Century Fox storage fire in 1937, but descriptions remain, and they are a hoot. If the title makes it sound more like a charming musical rather than a pageant of despair and death, it is with good reason considering the changes they made to it. This version is mostly about Esmeralda, no surprise since it features mega-star and sex symbol Theda Bara. Quasimodo has apparently been fixed by the time the movies starts – he is an ex-hunchback – by Frollo who is now a surgeon-scientist or something. In the end Esmeralda ends up back with the rich family she was stolen from, wed to Quasimodo. (Good grief.) Fun fact: It was shot on sets in Fort Lee, New Jersey, where most of Bara's pictures were produced. Another fun fact: The studios promoted Theda Bara as a mysterious, sexually voracious occultist born in Egypt. Actually she was Theodosia Goodman, a nice Jewish girl from Cincinnati.

The Brits made a version in 1922 called Esmeralda and again it focuses more on the sexy young dancer than anything else. It is a lost film. It starred an actress with the very non-Roma name of Sybil Thorndike who was forty years old at the time so she could have easily fit in with the other “teens” in the movie version of Grease.

The most famous version is The Hunchback of Notre Dame made in 1923 with Lon Chaney and Patsy Ruth Miller. It was the most expensive film Chaney ever made, costing $1,250,000 to produce, the equivalent of $22,345,833 today. You can watch the entire film on YouTube here, with commentary by film critic Farran Smith Nehme.

There is a 1939 version with Charles Laughton and Maureen O'Hara. It was very popular, earning $3.2 million, the equivalent of $70.3 million today. You can see his reveal here. This is the version I saw as a kid, since the silent Chaney version wouldn’t have been on broadcast television. I only saw the Chaney performance in film stills.

There is a 1956 French-Italian version with Anthony Quinn and Gina Lollobrigida. It was the biggest grosser in Paris in the 1956-1957 season. (By the way, it is the only film adaptation to use the book's original ending.)

There is a 1982 TV version with Anthony Hopkins and Lesley-Anne down. There are clips of it on YouTube.

There is a 1997 TV version with Mandy Patinkin and Selma Hayek. It looks like the entire movie is on YouTube.

And let’s not forget the 1996 Disney musical version, along with the sequel, Hunchback of Notre Dame II. Both of them are available on Disney+. That some liberties were taken with the story is strongly implied by the existence of the sequel, as you no doubt noticed. There are some who passionately believe this is the best animated film Disney ever made.

“It often gets lumped in with other underrated classics like Treasure Planet while being overshadowed by more popular Disney renaissance era movies like Tarzan,” wrote Nathanial Eker on Inside the Magic. “I guess a lot of Disney fans didn’t resonate with the whiplash-inducing tone and poor comic relief characters, but if you focus on what’s good, it’s some of the best Disney animation ever put to film.”

Spencer Legacy in ComingSoon.net says it is “undoubtedly one of the bravest and best movies that Disney has ever made. It’s a truly wild Disney movie.”

The mystery of Quasimodo

What do you think is going on here? This is a sad story with a severely disabled protagonist who is treated very badly, meanwhile nearly everyone is treating each other nearly as badly. Every male treats Esmeralda with contempt or tries to harm her, and don’t care that she is executed without justification, except Quasimodo, although he is willing to do her harm when ordered to. Why does this keep being made as a popular movie or TV entertainment?

And make no mistake, Quasimodo is the selling point here, not the plot. Sure, part of it is because the role of Quasimodo gives actors an opportunity to wear monster prosthetics and ham it up, but that doesn’t explain why everyone else – including the investors and the audiences – would be so engaged.

Especially because Quasimodo is not really the protagonist – he only plays a supporting role, albeit a colorful one – nor does he have much agency. He causes none of the major actions to occur, and he barely has a character arc. In some ways he is the audience stand-in, since he is a witness to many of the events and their consequences.

In conversation, many of my students pointed out how people identify with Quasimodo, that he was human and had feelings and was, in many ways, the "best" male character in the story and third best behind Esmeralda and her goat. I think that may be true, to a certain extent. But something else occurs to me. It is also true, I think, that he functions as a "monster" in the popular imagination, and the tension between seeing him as a frightening and lethal monster and seeing him as a caring and misunderstood outcast is what gives the story its snap for modern audiences. And, as the Disney version illustrates, we teach children this tension early.

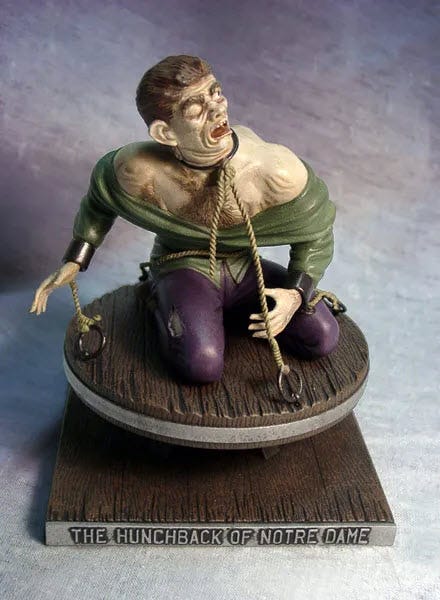

When I was a kid I liked old-school monster movies: Frankenstein, Dracula, Wolfman, Creature from the Black Lagoon, and so on. I had models of some of them I built and painted, and I'm pretty sure I had a Quasimodo one. It was him tied up on the pillory, kind of half the Chaney version, half the Quinn. I didn't see him as sympathetic as a kid, I saw him as a monster, something scary and dangerous. But maybe more fairly he was a "sympathetic monster" in that he was made scary and dangerous by how he was treated by society at large. You could say the same about Frankenstein and the Creature too. (Not Dracula, he was up to no good all day and night, and the Wolfman would kill you as soon as look at you.) In any case, as a kid I had no input that told me he was a normal, caring, thinking person who just looked very different and was deaf; the input I had from the media was that he was scary.

By the way, when I was looking for a photo of that old model kit, I stumbled across a discussion board devoted to the topic and found this 2009 post from "ChrisW" that sums it up pretty well:

"This is something that I've thought about from time to time. I love the Aurora monster kits, and right up there is their portrayal of 'The Hunchback of Notre Dame'. While not a very good likeness of Chaney Sr. as Quasimodo (if it was even intended to be), it captured a heartrending moment in the movie where the poor soul was hurt, humiliated and begging for water. And I guess that's my point. Did it ever bother you that the kit portrays a handicapped person being tortured? I'm not getting into political discussion, or calling the PC police to ban the kit. I was just wondering, did you ever look at it that way?"

This is why, perhaps, so many movies have altered the story to give it a happy, or at least happy-adjacent, ending. As a corrective. After all that suffering and unfairness, all that abuse and isolation, seeing Quasimodo and Esmeralda not end up so tragically gives the story some redeeming qualities the original lacked and modern audiences prefer. Although, to be honest, I’d be more sympathetic to those changes if the movies didn’t also do things like change Frollo from a church leader to some political figure, because film companies didn’t want to offend Catholic leadership. Or change Phoebus from a rapist and cad to a handsome hero.