In early March of 2021 the architect and writer Norton Juster died at the age of 91. He was the author of the beloved fantasy adventure book The Phantom Tollbooth, with illustrations by Jules Feiffer. Laura Miller – journalist and critic, co-founder of Salon – took the occasion to write an appreciation of Juster and his most famous work in Slate. It touched on many of the points she made in her article in The Paris Review in October 2011, on the fiftieth anniversary of the book. In the Slate version, however, she added an important new angle, which was to parse out some of the best aspects of The Phantom Tollbooth and present them as lessons for all writers.

“Every time I return to the book,” wrote Miller, “I marvel at how beautifully crafted it is, and not just for a kids’ book. There’s plenty that all kinds of writers can learn from Juster’s masterpiece.”

This article is based on Miller’s Slate piece, adapting and commenting on her ideas and insights. The six lessons:

Procrastination isn’t always your enemy

Sometimes procrastination is a way for our mind to work on solving a problem, or a way of telling us to go down a different path.

Juster wrote The Phantom Tollbooth when he was actually supposed to be writing a children's book about cities. He had even received a grant to write it. By any normal measure that cities book, which he was contractually obligated to complete, was his most important project and the one he should focus on.

Which he did not do.

This is a good example of the truism that, as Miller puts it, "The thing you write for fun will always be better than whatever you think is more important, serious, or expected of you."

This has turned out to be true in my own life. Back in the early 1980s I was working on a short feature-length, very ambitious, full of my ideas and my vision for what my films could be. One week in the middle of winter I just needed a break from all that ambition. I grabbed a ten-minute reel of discarded material in 16mm color and played with it, drawing and writing on it, mutating the sound. I was just having some creative fun. It went on to win multiple awards, screened in theatres and museums, and written about in several film and art publications. I never saw that coming, not for a moment.

"The secret, at least in my life," said Juster, "is that if you want to do something, you have to do something else to get away from that, and that’s the thing that turns out to be worthwhile.”

Not all geniuses are isolated, lone wolves

The cliché of the isolated genius working feverishly through his inspirations is, generally, hogwash.

We all benefit from creative collaborators, well-informed advisors, candid beta readers, and others who challenge and inspire us. Feeback helps us filter our own ideas.

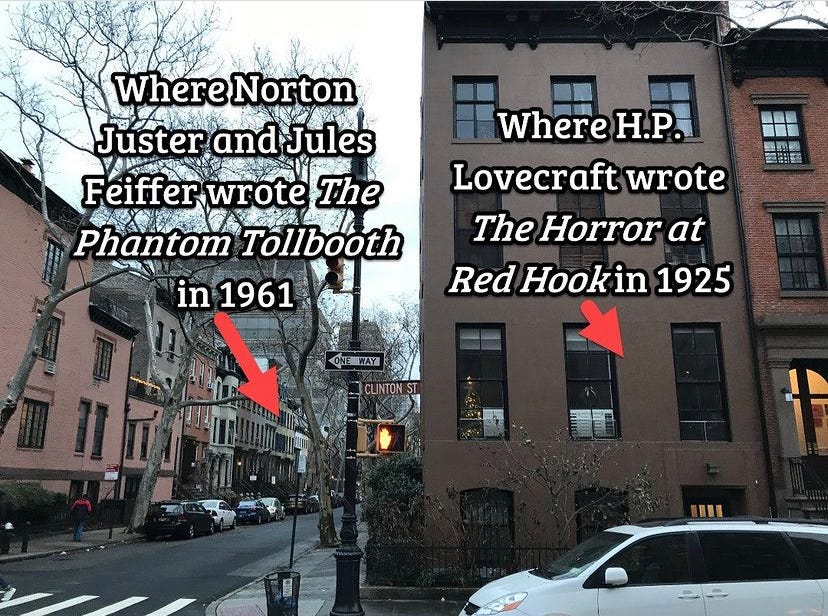

Juster was living in Brooklyn Heights when he wrote The Phantom Tollbooth in 1960, and his downstairs neighbor was the not-yet-famous cartoonist, Jules Feiffer.

(As it happens, Juster and Feiffer were living just around the corner from where H.P. Lovecraft was living when he wrote The Horror at Red Hook in 1925. But that's an entirely different story.)

Feiffer became interested in Juster's book and supplied some illustrations for it. This, in turn, inspired Juster to create increasingly fanciful characters and situations. Juster even tried to come up with things that would be impossible to depict visually, as a challenge to Feiffer.

“Such as the Triple Demons of Compromise,” notes Miller, as example of one of those impossible things. “One tall and thin, one short and fat, and the third exactly like the other two.”

Don’t be afraid of the big themes

Embrace the big themes. Just don't lean too hard on them. In The Phantom Tollbooth, the hero Milo learns that the Kingdom of Wisdom is in disarray because King Azaz of Dictionopolis is feuding with his brother The Mathemagician over whether letters are more important than numbers, or vice versa.

This is a sly nod to a famous lecture delivered by the chemist C.P. Snow in 1959. Titled “The Two Cultures” it was about the widening rift between the humanities and sciences.

"I didn’t lay it out as a thesis or anything," Juster said, "but it was fun having it in there. And it doesn’t get in the way of the story."

Think of how Lord of the Flies appears to be a boys’ adventure story but is actually a meditation on corruption and the lure of evil. Or how the Jazz Age character study The Great Gatsby is really about the hollowness and emotional bankruptcy at the center of an American dream based on money. Or how a light romantic period piece like Emma can explore how lack of self-awareness can lead us to become our own worst enemy, and threaten our destruction.

The power of big themes really shines in genre works. The themes can hide at first, lingering beneath the conventions and tropes. Until you realize that the book is actually about something significant and universal.

No literary genre ever really dies

Don't be afraid of dabbling with genres. “The right writer can revive any form,” says Miller.

The Phantom Tollbooth is full of allegory, which Miller calls “a misunderstood and unjustly maligned form.” Even when it was first published, allegory was generally felt to be out of fashion. Yet most readers don’t see it as such, because the allegory is layered in and never holds up the storytelling pace.

Storytelling genres and formats come in and out of fashion. But they don’t truly disappear. They periodically return. Sometimes they never really go away, but just remain in disguise.

A good example is the western novel (that is, novels set in the American west after the civil war). Hardly anyone reads westerns any longer. But the genre with its themes of cultural clashes, balancing the individual and the community, and the complexity of moral choices, lives on in crime, spy, and thriller novels. The format is just wearing a slightly different set of clothes.

Also, as the novelist Rick Moody put it, “Genre is a bookstore problem, not a literary problem.”

Procrastination sometimes actually is your enemy

Up above the point was made that procrastination can be a useful tool, an indicator that something is off about the project you are working on, or a call to do work that is more immediate and meaningful.

While all that holds true, there is Bad Procrastination as well. The kind that makes us chase shiny objects and be lost in rabbit holes online.

"As a child," writes Miller, "I found the Terrible Trivium, an exquisitely tailored dandy without a face, to be one of the creepiest characters I’d ever encountered. It was only as an adult that I appreciated how terrifying he truly is."

In The Phantom Tollbooth the Terrible Trivium diverts the heroes from their quest by charmingly enlisting their help with “a few small jobs.” Such as moving a pile of sand with just a set of tweezers. It sounds like the kind of office work many writers must do to earn a living wage, in order to support their writing career.

Juster said the Trivium was inspired by his tendency to sit at his desk and "Realize that I have to straighten out the paper clips, or there’s something happening out the window, or a shopping list has to be compiled.”

It used to be paperclips. Now it’s the entire damn internet calling us to doomscroll instead of accomplishing anything. Woe is us.

As Mark Twain said, “Never put off till tomorrow what may be done day after tomorrow just as well.”

Good writing is as much about what you don’t say

You don't have to spell everything out. Not every thought needs to be explained. Sometimes, as they say, action is character and that is sufficient.

The Phantom Tollbooth conveys a fuller world by leaving things out, leaving them unexplained. A good example is the tollbooth itself, which mysteriously appears for the hero Milo. We never find out who sent it, nor do we need to.

Writes Miller, "That the tollbooth arrives when needed and departs after it has served its purpose is much more satisfying than, say, a backstory about it being a gift from Milo’s wise but eccentric aunt."

Miller notes that the same goes for description. She talks about a scene which takes place at the Fortress of the Soundkeeper.

"Milo is given an envelope that supposedly contains 'the exact tune George Washington whistled when he crossed the Delaware on that icy night in 1777,’” explains Miller. “When Milo opens the envelope to peer inside, ‘Sure enough, that’s exactly what was in it.'"

And that’s all the description the reader needs. Anything more – any attempt to convey what that whistle sounded like, or what the tune was called – would ruin the perfection of what the reader already concocted in their heads.

By not giving any more information than that, says Miller, "Juster creates the space for the reader’s imagination to flourish.”

By the way, writing wasn’t Norton Juster’s profession, architecture was. But he had books in him, and he wrote them. That right there is perhaps the most important lesson he has to give us: just do it.