I was thinking the other day about books that had some personal significance to me while also being influences on my writing. If I had to choose just a handful, what would they be?

I’m specifically talking about novels here, opening the door to non-fiction would make the exercise unmanageable!

For a book to have the personal impact I’m talking about, it had to: reflect me and my character enough to offer something of a revelation; or cause me to learn or reconsider things about the world that had long-lasting effects.

For a book to influence my writing, it had to offer an example, a path forward, whether in conception or craftsmanship, that I consciously applied. A book doesn’t have to be a “great” work to do this, nor does it need be a paragon of literary style.

So here are five titles I chose. Maybe if I re-make this list a year from now the books would be different, but these will do today. In order of publication, and in order of when I read them.

Red Harvest (1929), Dashiell Hammett

I’ve written about The Glass Key in this space, how it was a huge influence and had such personal resonance. But I came to Hammett here first. This is the story of a small city torn apart by violent battles between capitalist power brokers, corrupt officials, and rival criminal gangs. The protagonist is the unnamed “Continental Op,” an operative of the Continental Detective Agency, a blueprint for tough, unsentimental detectives for decades to come. The story is one long fever dream of bad behavior, gun play, colorful characters, betrayal, extortion, drug and alcohol abuse, murder, and sex. Dinah Brand is, perhaps, the most intriguing femme fatale in American crime fiction. The closest thing to the style of this novel was Hemingway, who never offered anything this entertaining. Dorothy Parker read this and declared Hammett her hero. André Gide called it “the last word in atrocity, cynicism, and horror.” It influenced a horde of films, including Yojimbo, A Fistful of Dollars, Miller’s Crossing, Brick, and Last Man Standing.

Catch-22 (1961), Joseph Heller

I reread this multiple times. It solidified what my teenaged mind had already sensed, that life was absurd, that people in charge often had no idea what they were doing, and societal structures are designed to repress originality and eliminate actual choice. The novel is funny, paradoxical, and quite clever in its use of circular motifs. Even minor characters are fully-formed and unforgettable, often with ridiculous names. It’s all so much fun until, eventually, we learn why characters are so traumatized, because the horrors of war have warped them. Many characters eventually die, some by war, some by murder, some in spectacularly gruesome ways. God is considered to be either incompetent or malicious, maybe both. The real enemy might be your commanding officer. This is satire that is also a statement of rage. Can you imagine the impact this book had on me, a smart and independent-minded kid in junior high who had being drafted into the army to fight in the Vietnam War to look forward to?

Interview with the Vampire (1976), Anne Rice

This has entered the culture so thoroughly that it’s hard to imagine the impact it would have had on someone like me who read it when it first came out. As a kid I liked horror movies and scary short stories, but the representations of vampires in those were limited. They were the vague undead, and always somewhat camp. But Rice took a tired genre and its tropes, and exploded them into a rich tapestry of a fully formed community in the shadows. She gives her vampires distinct, complex personalities. They had a life before they turned, and a life after. They are interesting people, who struggle with morals and urges, emotions and fears. This was, in other words, analogous to my new life as a working artist, on the margins, with equally disempowered friends. There are some unforgettable set-pieces, such as the terrifying return of a vengeful Lestat. There are brilliant takes on what a subterranean culture of vampires might contain, such as the truly disturbing vampire child Claudia, and the strange, feral old-world vampires who frighten even Louis.

Pattern Recognition (2003), William Gibson

This was Gibson’s first book set in the current day. It features a protagonist who has extraordinary sensitivity to corporate branding and logos and other iconography of the modern global economy. With the paranoia and anxiety of the western world post-9/11 as backdrop, the novel explores how people can easily find patterns in the overwhelming wealth of images and data flooding over all of us, if they only look hard enough. “Meaning” is everywhere and nowhere; messages no longer require a sender, just a self-designated receiver to create the message out of nothing. The book anticipates the rabid lunacy of today’s conspiracy fringe like QAnon; it also anticipates the prevalence of pretending to be female online, and he invented the word “gender-baiting” to describe it. (Gibson has made anticipating societal trends something of his own personal cottage industry.) When I read this, I was early in my final-phase career as a global marketing communication leader for international business services firms, so this living autopsy of the advertising/branding ecosystem hit home.

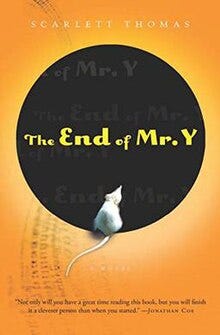

The End of Mr. Y (2006), Scarlett Thomas

The story of PhD student Ariel Manto who goes down a deep, surreal rabbit hole. There is a cursed book, the use of homeopathy to open portals to a parallel universe called the Troposphere where consciousness is networked and you can enter the minds of other people. There are foreign agents who want to kill her and others who help her and others who want secrets kept. There are ruminations on quantum physics and deconstructionist theory and phenomenology. This is mystery and adventure and thriller and science fiction and fantasy all put into a blender, Thomas swinging for the fences and connecting. “This is more fun than it sounds,” said the New York Times in its review, “and more fun than it has any right to be.” The book title is a pun; the main character is an anagram for “I am not real.” Since I read this, I’ve discovered my weak spot for smart, genre-blending work with aspirational themes, such as Stuart Turton’s The Last Murder at the End of the World, and Stephanie Feldman’s Saturnalia.